In this article, we introduce several important extensions of PCF. All are obtained by adding new types.

The first extension is a very simple one, a type unit with only one element. The second extension is sum, or disjoint union, types. With unit and disjoint union types, we can define $bool$ as the disjoint union of $unit$ and $unit$. This makes the primitive type $bool$ unnecessary.

The third extension is recursive type definitions. With recursive type definitions, unit, and sum types, we can define $nat$, making the primitive type $nat$ also unnecessary.

Unit type

We add the one-element type unit to PCF, or any language based on typed lambda calculus, by adding $unit$ to the type expressions and adding the constant $*:unit$ to the syntax. The equational axiom for $\ast$ is

\[M:unit = *. \tag*{($unit$)}\]Intuitively, this axiom says that every element of type $unit$ is equal to $\ast$. In other words, the type $unit$ contains only one element that is $\ast$. This seems not very interesting, but it will be surprisingly useful in combination with sums and other forms of types!

Sum type

Definition

The sum type $\sigma + \tau$ is defined as the disjoint union of types $\sigma$ and $\tau$.

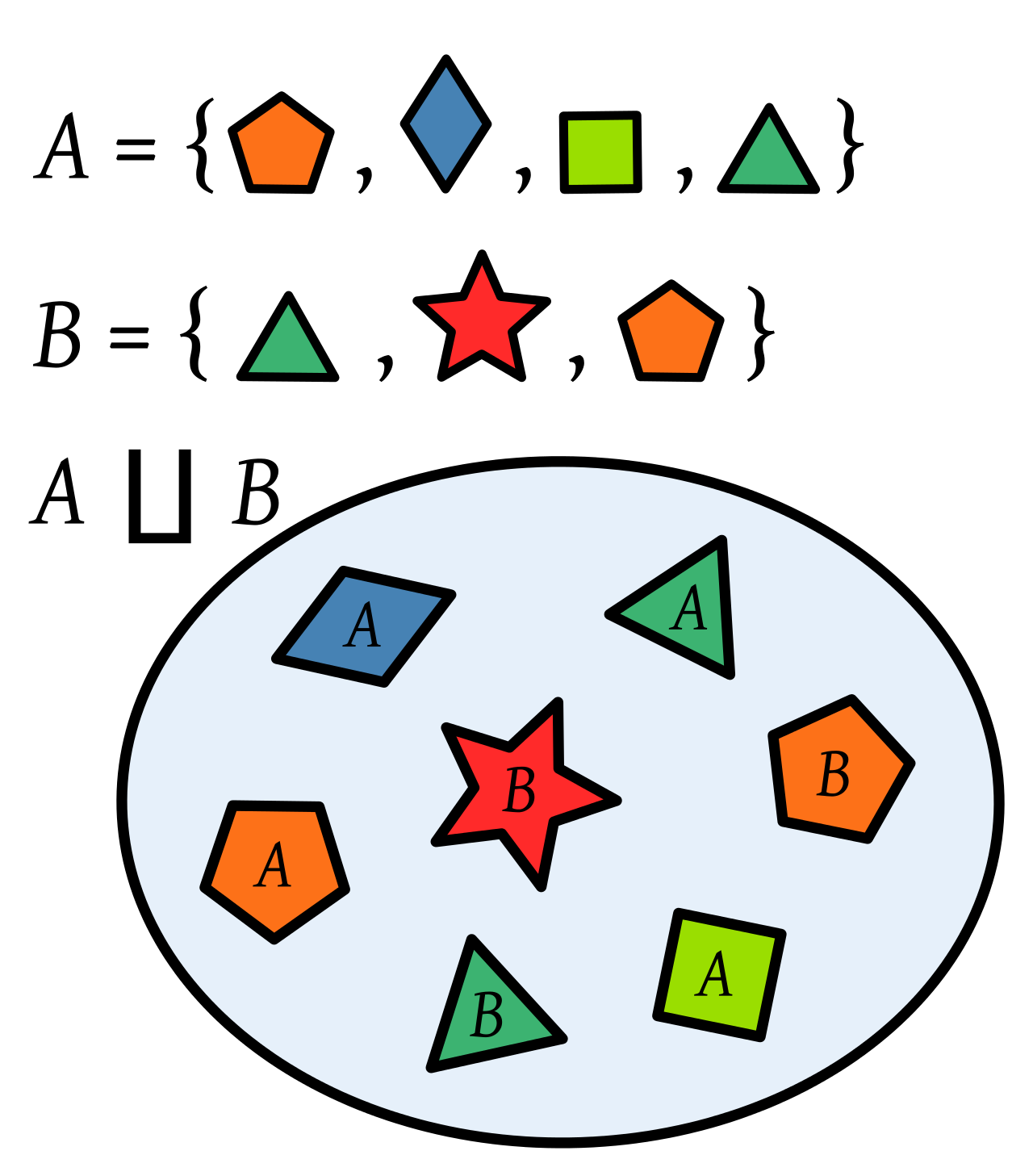

In mathematics, the disjoint union $A\sqcup B$ of the sets A and B is the set formed from the elements of A and B labeled (indexed) with the name of the set from which they come. So, an element belonging to both A and B appears twice in the disjoint union, with two different labels. Below is an illustration to the disjoint union.

For example, we may think of the sum type $int + int$ as the collection of “tagged” integers, with each tag indicating whether the integer comes from the left or right $int$ in the sum.

There are two kinds of functions associated with sums. The first kind are injection functions. For any types $\sigma$ and $\tau$, the injection functions $\mathbf{Inleft}^{\sigma,\tau}$ and $\mathbf{Inright}^{\sigma,\tau}$ have types

\[\begin{split} \mathbf{Inleft}^{\sigma,\tau} : \sigma \rightarrow \sigma + \tau \\ \mathbf{Inright}^{\sigma,\tau} : \tau \rightarrow \sigma + \tau \end{split}\]Intuitively, the injection functions map $\sigma$ or $\tau$ to the sum $\sigma + \tau$ by tagging elements.

Considering that the operations on tags are encapsulated, we never say exactly what the tags are. But we can give names to tages and borrow pairing syntax to help us understand: assume the function $\mathbf{Inleft}^{\sigma,\tau}$ tags “left”, and the function $\mathbf{Inright}^{\sigma,\tau}$ tags “right”, then we have

\(\begin{split} &\mathbf{Inleft}^{\sigma,\tau} \: x \:\stackrel{\text{def}}{=}\: \langle x,left \rangle \\ &\mathbf{Inright}^{\sigma,\tau} \: y \:\stackrel{\text{def}}{=}\: \langle y,right \rangle, \end{split}\)

where \(x:\sigma, \:y:\tau\), and both $\langle x,left \rangle$ and $\langle y,right \rangle$ are of type $\sigma + \tau $.

The second kind of functions are case functions. The $\mathbf{Case}$ function applies one of two functions to an element of a sum type. The choice between functions depends on which type of the sum the element comes from. For all types $\sigma$, $\tau$ and $\rho$, the case function $\mathbf{Case}^{\sigma,\tau,\rho}$ has type

\[\begin{split}\\ \mathbf{Case}^{\sigma,\tau,\rho}:(\sigma + \tau) \rightarrow (\sigma \rightarrow \rho) \rightarrow (\tau \rightarrow \rho) \rightarrow \rho \end{split}\]Intuitively, \(\mathbf{Case}^{\sigma,\tau,\rho}\) is a function accepting three arguments: a sum type term and two functions. The expression \(\mathbf{Case}^{\sigma,\tau,\rho} \: x \: f \: g\) inspects the tag on the first argument $x$ and applies (1) function $f$ if $x$ is from $\sigma$ or (2) function $g$ if $x$ is from $\tau$. The main equational axioms are

\[\mathbf{Case}^{\sigma,\tau,\rho} \: (\mathbf{Inleft}^{\sigma,\tau} \: x) \: f \: g = f\: x\tag*{$(case)_1$}\] \[\mathbf{Case}^{\sigma,\tau,\rho} \: (\mathbf{Inright}^{\sigma,\tau} \: x) \: f \: g = g\: x\tag*{$(case)_2$}\]In the later description, we will drop the type superscripts from injection and case functions when the type is either irrelevant or determined by context.

Eliminate Boolean

As an illustration of $unit$ and sum types, we will show how to eliminate $bool$ in PCF by adding $unit$ and sum types.

We can define $bool$ by

\[bool \:\stackrel{\text{def}}{=}\: unit + unit\]and boolean values $true$ and $false$ by

\[\begin{split} true &\:\stackrel{\text{def}}{=}\: \mathbf{Inleft} \: * \\ false &\:\stackrel{\text{def}}{=}\: \mathbf{Inright} \: * \end{split}\]The remaining basic boolean expression is conditional, \(\text{if } ... \text{ then } ... \text{ else} ...\). We may consider this sugar for $\mathbf{Case}$, as follows:

\[\text{if } M \text{ then } ... \text{ else} ... \:\stackrel{\text{def}}{=}\: \mathbf{Case}^{,,\rho} \: M \: (K_{\rho,unit} \: N) \: (K_{\rho,unit} \: P),\]where $N,P$ are of type $\rho$ and $K_{\rho,unit}$ is the lambda term \(\lambda x: \rho.\: \lambda y: unit.\:x\) that produces a constant function.

Recursive Types

In some programming languages, it is possible to define types recursively. An example is Ocaml, which has recursive type declaration. The natural number type can be defined in Ocaml as follows.

1

type nat = Zero | Succ of nat

This Ocaml expression defines the type nat as either Zero or a successor of a value in nat.

In PCF, we may similarly define the $nat$ type by the following grammar.

\[nat ::= unit \mid unit + nat\]Note that the $+$ symbol means “disjoint union” in type expressions, instead of “add”.

Here, we use $unit$ type to represent the numeral $0$.

Considering that $nat$ occurs in the both side of $::=$, as what we have done during the recursive function section, it is convenient to convert this into a proper definition by moving the “loop” over to the right-hand side. We do this by introducing an explicit recursion operator $\mu$ for all types

\[nat ::= \mu t.(unit \mid unit + t).\]Intuitively, this definition is read, “let $nat$ be the smallest type $t$ satisfying the equation \(t = \mu t.(unit \mid unit + t)\).”

In general, we use $\mu t.\sigma$ to represent the smallest type (collection of values) satisfying the equation

\[t = \sigma,\]where $t$ and $\sigma$ are type variables, and $t$ will generally occur in $\sigma$. In this type expression $\mu t.\sigma$, we say $t$ is bound by operator $\mu$, and $\sigma$ is free.

Using type variables and the type expression $\mu t .\sigma$, we can now give the type expressions of PCF. If we eliminate $bool$ and $nat$ by adding $unit$, sum, and recursive types, then we have PCF type expressions generated by the following grammar:

\[\sigma ::= t \mid unit \mid \sigma+\sigma \mid \sigma \times \sigma \mid \sigma \rightarrow \sigma \mid \mu t.\sigma\]