In this article, we recover some notation and mathematical conventions that will be frequently used in subsequent articles. We assume readers have basic knowledge of grammar and logic.

Grammars

Grammars provide a convenient method for defining an infinite set of expressions.

Consider the simple language of numeric expressions given by the grammar

\[\begin{split} &e ::= n \mid e+e \mid e-e\\ &n ::= d \mid nd\\ &d ::= 0 \mid 1 \mid 2 \mid ... \mid 9 \end{split}\]The symbol \(::=\) is used in grammars to indicate possible forms of expressions.

where the first symbol \(e\) is the start symbol. It is the symbol you need to begin with if you want to derive a well-formed expression from the rules of a grammar.

The way a start symbol is used is that we begin with \(e\), and continue to replace a symbol that occurs on the left of the ::= with one of the strings between vertical bars on the right until none of the nonterminals \(e\), \(n\), or \(d\) are left.

Nonterminals are symbols that occurs on the left of the \(::=\).

For example, here are two derivations of well-formed expressions:

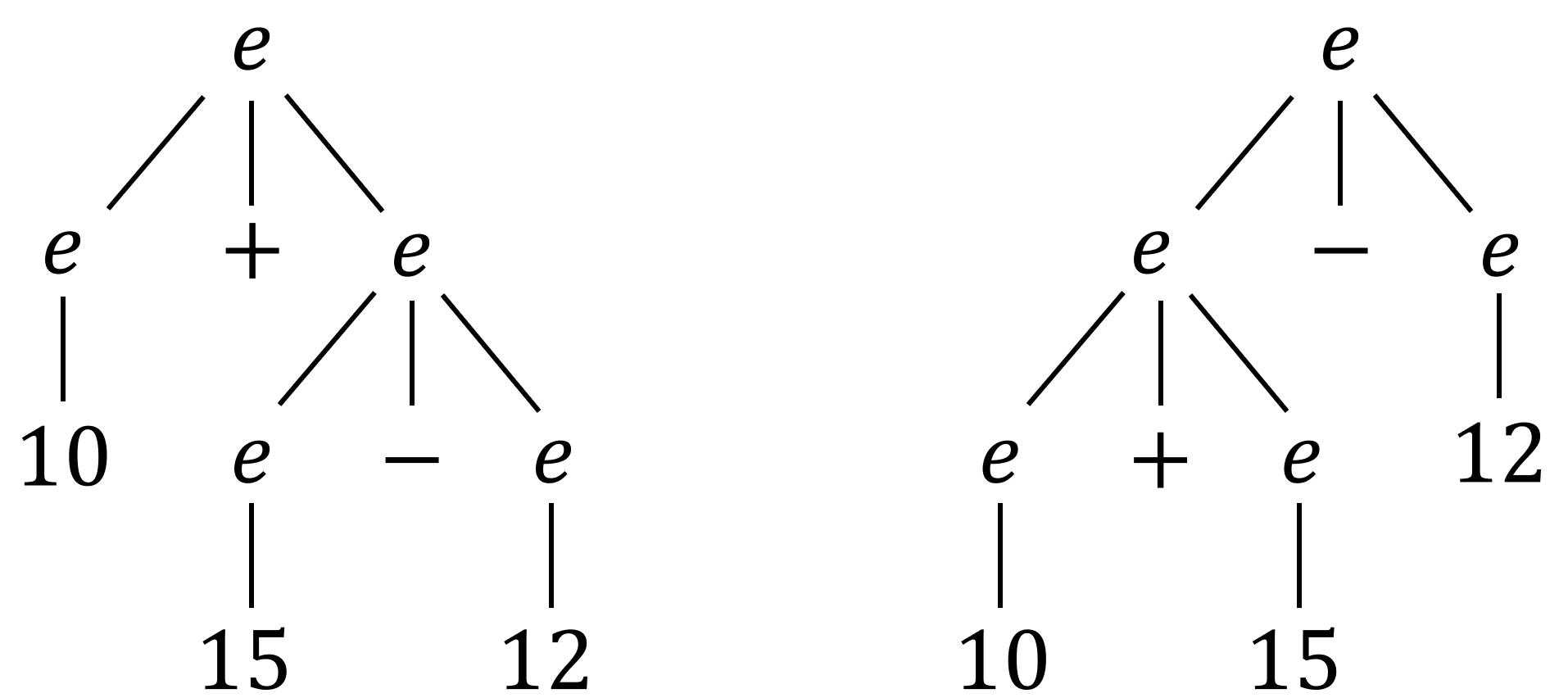

\[e \rightarrow n \rightarrow nd \rightarrow dd \rightarrow 2d \rightarrow 25\] \[e \rightarrow e+e \rightarrow e+e-e \rightarrow ... \rightarrow n+n-n \rightarrow ... \rightarrow 10+15-20\]It is often convenient to represent a derivation by a tree. This tree, called the parse tree of a derivation, is constructed using the start symbol as the root of the tree. For example, the expression \(10+15-20\) can have the following two kinds of parse trees.

An important fact about the parse tree is that each corresponds to a unique parenthesization of the expression. Specifically, the left parse tree corresponds to \(10+(15-12)\) while the right corresponds to \((10+15)-12\).

A grammar is said to be ambiguous if there is some expression with more than one parse tree. If every expression has exactly one parse tree, the grammar is unambiguous.

Parse trees are also called concrete syntax trees.

Correspondingly, there is another term that is frequently mentioned in the software engineering field, called the abstract syntax tree (AST), which is a kind of parse tree that discards unimportant syntax details. For instance, AST only uses a single node to represent some complex syntactic structure, like an if-condition-then statement. See this wiki page for more.

Logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning, including both formal and informal logic.

Informal logic uses non-formal criteria and standards to analyze and assess the correctness of arguments. It is expressed in natural languages and mainly focuses on everyday discourse. It includes questions about the role of rationality, critical thinking, and the psychology of argumentation.

Formal logic is the study of inferences or logical truths. Different from informal logic, it uses formal languages to examine how conclusions follow from premises due to the structure of arguments alone, independent of their topic and content.

Logic has been studied since ancient Greece. The work of Aritotle and Stoics was considered the main system of logic in the western world until it was replaced by modern formal logic, which has its roots in the work of late 19th-century mathematicians, such as Gottlob Frege and David Hilbert.

Programming Language theory has a profound connection with modern formal logic. Here, we are going to briefly recover three most influential formal logical systems — propositional logic, first-order logic, and higher-order logic.

Simply speaking, propositional logic is a system that only considers logical relations between propositions. First-order logic also takes the internal parts of propositions into account, like predicates and quantifiers. And higher-order logic admits quantification over sets that are nested arbitrarily deeply.

Just keep reading the following contents if above summary appears unfamiliar to you.

Propositional Logic

The propositional logic (which sometimes is also called zeroth-order logic) deals with propositions and relations between propositions.

A proposition is defined as a declarative sentence that is either true or false, but not both. For example,

- The sun rises in the east and sets in the west.

- ‘e’ is a vowel.

- $1 + 1 = 3$

- $x + 1 = 3$

these sentences are propositions except the last one. The first two are true, the third one is false, but the last one may be true or false.

To represent propositions in a symbolical way, propositional variables are used. By convention, these variables are written using small alphabetes such as $p,q,r,s$.

The common relations between propositions are negation ($\lnot$), conjunction ($\land$), disjunction ($\lor$), implication ($\to$), and biconditional (or double) implication ($\leftrightarrow$). For example, the proposition

\[(p \land q) \to (p \lor q)\]says that “if $p$ and $q$ are both true, then $p$ or $q$ is true,” and we can easily verify that this is a true proposition.

First-Order Logic

First-order logic — also called predicate logic — adds predicates and quantifiers on the basis of propositional logic.

A predicate is a symbol that represents a property or a relation. For instance, in the first-order formula $P(x)$, the symbol $P$ is a predicate that applies to the non-logical variable $x$.

Here lists some simple predicates:

- $P(x)$ : $x$ is high.

- $Q(x,y)$ : $x$ owes money to $y$.

- $R(x,y,z)$ : $x+y+z < 3$

As you can see, the truth value of a predicate depends on the values of its arguments.

A quantifier is a way to state that a certain number of elements fulfill some criteria. For example, in the sentence “every natural number has another natural number larger than it,” the word “every” is a quantifier. Therefore, this is a quantified proposition.

The two quantifiers most widely used are the universal quantifier ($\forall$) and the existence quantifier ($\exists$).

The universal quantifier is used to claim that for elements in a set, the elements all match some criteria. We write \(\forall\: x \in X . P(x)\) to mean “For every $x$ that is a member of set $X$, $P(x)$ is true.”

The existential quantifier is used to claim that for elements in a set, there exists at least one element that matches some criteria. We write \(\exists \: x \in X .P(x)\) to mean “There exists an element $x$ that is a member of set $X$, so that $P(x)$ is true.”

Higher-Order Logic

A higher-order logic is a form of logic that is distinguished from first-order logic mostly by allowing quantification over logical variables.

That is, the expression \(\exists \: P .P(x)\) is a legitimate sentence of higher-order logic, where $P$ is a predicate variable.

As a result, higher-order logic has greater expressive power than first-order logic. For example, if we define predicates

\[\begin{split} &\text{Cube}(x) : x \text{ is a cube}\\ &\text{Tet}(x) : x \text{ is a tetrahedron} \end{split}\], there is no way in first-order logic to identify the set of all cubes and tetrahedrons. But the existence of this set $P$ may be asserted in higher-order logic as

\[\exists \: P .\forall \: x. (P(x) \leftrightarrow (\text{Cube}(x) \lor \text{Tet(x)})).\]Accompanied with this high flexibility introduced by higher-order logic, the equality verification between expressions becomes much harder. Gérard Huet has shown in 1970s that there can be no algorithm to decide whether an arbitrary equation between higher-order expressions has a solution.

Proof and Induction

Proof System

In logic, a proof system is built to prove statements, and it is the core strucutre the logicians devoting to build during their study.

A Hilbert-style proof system consists of axioms and proof rules. An axiom of a proof system is a formula that is provable by definition. An inference rule asserts that if some list of formulas are provable, then another formula is also provable. A proof, therefore, is a structured object built from formulas according to constraints established by a set of axioms and inference rules.

These definitions may seem obscure at first glance. Now let’s take a closer look at this proof system.

Axioms and inference rules are generally written as schemes, representing all formulas or proof steps in a given form. We start from the most basic axiom scheme — the reflexivity axiom for equality.

\[e=e \tag*{($ref$)}\]This axiom scheme asserts that every equation of the form \(e=e\) is an axiom. For example, \(x = x\), \(y=y\), and \(3=3\) axioms under this scheme.

An inference rule scheme generally has the form

\[\frac{A_1 \: A_2 \:...\:A_n}{B}\]meaning that if we have proofs of formulas of the form \(A_1\), \(A_2\), and \(A_n\), then we can combine these proofs to obtain a proof of the corresponding formula \(B\).

For example, the inference rule for transitivity of equality is written

\[\frac{e_1 = e_2 \quad e_2 = e_3}{e_1=e_3} \tag*{($trans$)}\]This means that if we have a proof of \(3+5=8\) and a proof of \(8 = 2^3\), then we can combine these two proofs to form a proof of the equation \(3+5 = 2^3\).

Technically, the formulas above the horizontal line are called antecedents of the proof rule, and the formula below the line are called the consequence.

Formally, a proof can be defined as a sequence of formulas, with each formula either an axiom or following from previous formulas by a single inference rule. Next, we will give a concrete example of proof system and show how to induce on it. In other words, we want to prove some property for a specific proof system.

Induction on Proof

Now, we are going to show how to do induction on a proof system, so that we can get some useful properties of this system.

A Simple Proof System

Let us consider a simple proof system for inequalities \(e \leq e'\), where \(e\) and \(e'\) are generated by the following grammar.

\[e ::= 0 \mid 1 \mid e+e \mid e*e\]This grammar suggests that we only consider the expression representing a form of mathematical addition and multiplication operations on numbers 0 and 1. For example, $1 * 0 + 1$ is a valid expression under our grammar, while $10 + 1$ and $1 - 0$ are not valid.

The proof system has two axioms, one stating that \(\leq\) is reflexive

\[e \leq e \tag*{($refl$)}\]and the other stating that \(0\) is no larger than any other expression.

\[0 \leq e \tag*{($0 \leq$)}\]Moreover, there is a transitivity rule and two additional inference rules giving monotonicity of addition and multiplication.

\[\frac{e \leq e' \quad e' \leq e''}{e \leq e''} \tag*{($trans$)}\] \[\frac{e_1 \leq e_2 \quad e_3 \leq e_4}{e_1 + e_2 \leq e_3+e_4} \tag*{($+mon$)}\] \[\frac{e_1 \leq e_2 \quad e_3 \leq e_4}{e_1 * e_2 \leq e_3*e_4} \tag*{($*mon$)}\]This is a relatively weak proof system for the ordinary ordering on natural numbers. However, it is sufficient to illustrate some basic ideas!

Prove Soundness

A very common property to establish for a proof system is that every provable formula is true. This is called soundness of the proof system.

We want to prove the soundness of our example proof system for \(\leq\). More precisely, we prepare to show that the property

\[\begin{split} P(\pi) \stackrel{\text{def}}{=} &\text{ if } \pi \text{ is a proof of } e \leq e' \text{ then for all values of variables,}\\ &\text{ the value of } e \text{ is } \leq \text{ the value of } e' \end{split}\]In this property definition, the first \(\leq\) symbol is a relationship we just designed under a proof system, and the second \(\leq\) symbol is the mathematical “less than or equal to” sign, which we have learned since primary school.

holds for every proof \(\pi\) in our system. In other words, if we can prove a formula, then the formula is true, for all possible values of the variables that occur in the formula.

The first step is to establish the property \(P\) for each of the axioms. This is easy, since whatever values we give to the variables occurring in an expression \(e\), the value of \(e\) is some specific natural number. Based on our mathematical knowledge, we always have \(e \leq e\) and \(0 \leq e\).

Then we try to do induction using three inference rules. We first show the case for \((+mon)\) rule. Suppose that we may prove inequalities \(e_1 \leq e_2\) and \(e_3 \leq e_4\). Let us pick values \(n_1, n_2, n_3, n_4 \in \mathbb{N}\) for the variables that occur in \(e_1, e_2, e_3, e_4\), such that \(n_1 \leq n_2\) and \(n_3 \leq n_4\). It is easy to see that therefore \(n_1 + n_2 \leq n_3+n_4\) . Of course we can prove something similar for \((*mon)\) and \((trans)\). Considering this reasoning applies to all possible values of the variables, the property \(P(\pi)\) holds for proofs ending in any inference rules in our proof system.

We will discuss proof systems with more details in a later article Easy Foundations for Programming Languages VIII — Proof Systems.